A drug that causes animals to grow new teeth is heading to clinical trials. If it proves safe and effective in people, it could one day allow us to regenerate teeth lost to injury, disease, or old age.

The challenge: 17% of Americans will lose all of their teeth by the time they’re 65, and the vast majority of us will lose at least some teeth as we get older.

While dentures or implants can replace these lost teeth, one can feel less-than-natural, and the other requires surgery.

“The idea of growing new teeth is every dentist’s dream.”

Katsu Takahashi

What’s new? Researchers in Japan are developing a medicine they believe may enable people to grow new teeth to replace ones they’ve lost. They’ve already proven it can trigger tooth growth in mice and ferrets and have now announced plans to launch clinical trials in July 2024.

“The idea of growing new teeth is every dentist’s dream,” lead researcher Katsu Takahashi told the Mainichi. “I’ve been working on this since I was a graduate student. I was confident I’d be able to make it happen.”

How it works: In 2007, the researchers reported the discovery that mice with underexpressed USAG-1 genes also had extra teeth. The gene’s protein plays a role in the development of many body parts, though, so simply knocking it out to trigger tooth growth wasn’t an option.

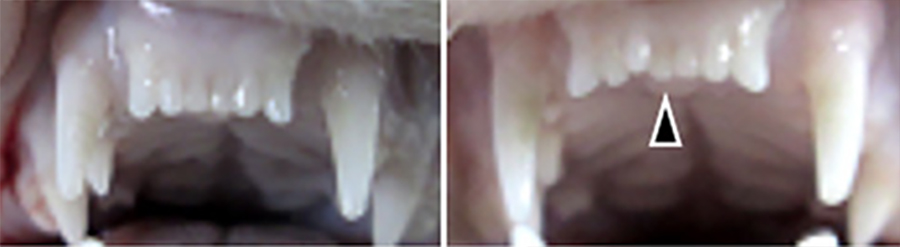

Instead, the researchers started testing different monoclonal antibodies — lab-made proteins designed to bind to certain molecules — on mice with a condition that caused them to be born with fewer teeth than normal. Their hope was that they’d find one that could disrupt the USAG-1 protein’s activity in a way that would let the animals grow new teeth while remaining healthy.

In 2021, they reported the discovery of such an antibody, noting that it also triggered tooth growth in ferrets, which, according to Takahashi, have “similar dental patterns to humans.”

Looking ahead: The researchers are now preparing to test the safety of their monoclonal antibody, TRG035, in people with congenital tooth agenesis, the same condition as the mice in the 2021 study. If proven safe, trials testing its efficacy would follow.

If the therapy is approved, the researchers envision it first being used to grow new teeth in 2 to 6 year olds with signs of agenesis. Eventually, they think it could be administered to people who were born with the right number of teeth, but lost some of them in adulthood.

“[W]e’re hoping to see a time when tooth-regrowth medicine is a third choice alongside dentures and implants,” said Takahashi.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].