Synchron, a company that’s competing with Elon Musk’s Neuralink and other firms to bring brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) to market, has become the first in its industry to enroll a patient in a clinical trial approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

The early feasibility study will assess the safety and efficacy of permanently implanted BCIs, which aim to restore functionality to paralyzed people by enabling them to control digital devices using only their thoughts.

A milestone for the BCI industry: Since the 1990s, a small but growing body of research has shown that BCIs can enable paralyzed people to use their thoughts to type words, control a computer cursor, and move robotic hands and arms. In more recent years, BCIs have even helped paralyzed people regain limb movement and the sense of touch.

But the industry is still young. Before BCIs can begin restoring functionality to the more than 5 million people in the US who suffer from paralysis, companies like Synchron and Neuralink need to demonstrate that the technology is safe, effective in non-research settings, and able to be produced at affordable prices.

Sychron’s clinical trial represents a major step toward clearing regulatory and practical hurdles for the BCI industry.

How BCIs translate thoughts into action

All BCIs work in the same general way: A device monitors brain activity, decodes that activity into data representing desired action, and then sends a command to a body part or an external device to perform the desired action. In other words, BCIs fix the broken communication links between brain and body.

Translating brain activity into commands takes some training. Using machine learning-based software, the BCI system eventually learns to link specific expressions of brain activity with a target action.

One area where BCIs differ is invasiveness. The most invasive devices need to be implanted under the skull, which requires open brain surgery. Synchron’s interface, called the stentrode, is still invasive, but it takes an arguably more appealing approach by implanting the device in the chest, similar to a cardiac pacemaker procedure. This method is not only safer, but also greatly increases the number of physicians who would be able to implant the interfaces into patients.

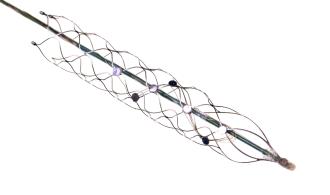

The strentrode

But how does a chest implant with the brain? Starting in the chest, a tiny stent containing sensors is routed through the jugular vein and up into the brain’s blood vessels, where it stays permanently and eventually fuses with the blood vessel.

Stents have been used since the 1980s to treat heart disease by ensuring arteries stay open, and more recently to treat intracranial idiopathic hypertension. But the strentrode is the first to use stents as part of a BCI.

“What we’re doing differently is using the blood vessels as the natural highway into the brain and lacing the inside of the blood vessels with electrodes, or sensors, that can record activity from the brain,” Synchron CEO Thomas Oxley said in a video.

The signals recorded by the sensors inside the blood vessels then travel down to the implant in the chest, which wirelessly transmits data to external digital devices. In short, it’s a Bluetooth connection for the brain.

For Graham Felstead, a 75-year-old man paralyzed as a result of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), the strentrode helped him regain the ability to send emails, shop, and bank online. As part of a 2019 Synchron clinical trial in Australia, Felstead was implanted with the stentrode, becoming the first person to ever be implanted with a BCI that’s implanted into the brain’s blood vessels.

Synchron’s recently approved early feasibility study comes in the wake of that successful Australian clinical study, in which the stentrode enabled four paralyzed patients to perform basic tasks on a computer: control cursor clicks with more than 90% accuracy and type at least 14 characters per minute.

That’s still not quite the futuristic vision promised by others in the BCI industry. For some companies, the long-term goal is to create devices that transform how we communicate, such as by enabling telepathy or the ability “to share full sensory and emotional experiences, not just photos,” as Mark Zuckerberg said in 2015.

Synchron CEO Thomas Oxley said the company’s “north star is to achieve whole-brain data transfer.” But for now, the focus is on the motor cortex, where simpler and more affordable BCIs could soon help improve quality of life for people with paralysis.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].