On 10 May of this year, half a dozen African presidents came to Kazungula to inaugurate a bridge. Not just any bridge, then: the Kazungula Bridge, linking Zambia to Botswana across the mighty Zambezi River, is a game-changer. It has the potential to redirect the flow of traffic throughout much of Africa as well as provide a major boost to the entire region’s economy.

A gentle but curious curve

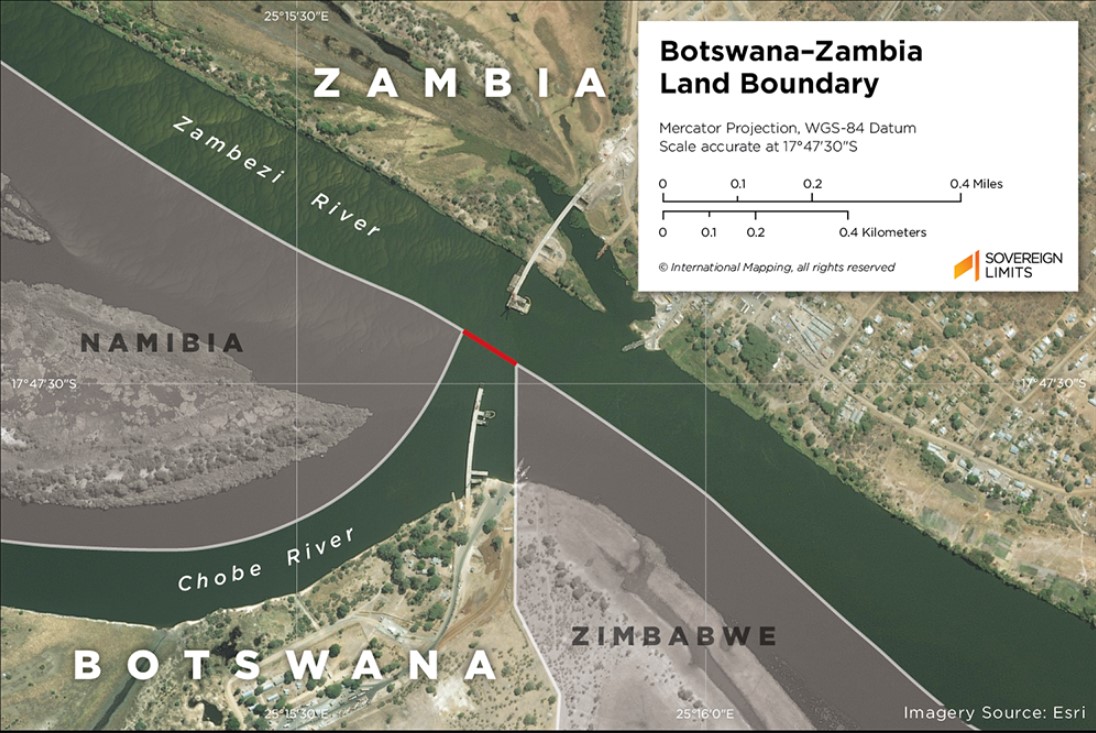

There’s more going on with the Kazungula Bridge, though. As it connects one country to the other, it makes a gentle but curious curve. There is no structural reason for it, only a geopolitical one: this is to avoid touching two other countries located on either side of the bridge. Because the bridge passes by the point where the world’s only international quadripoint isn’t.

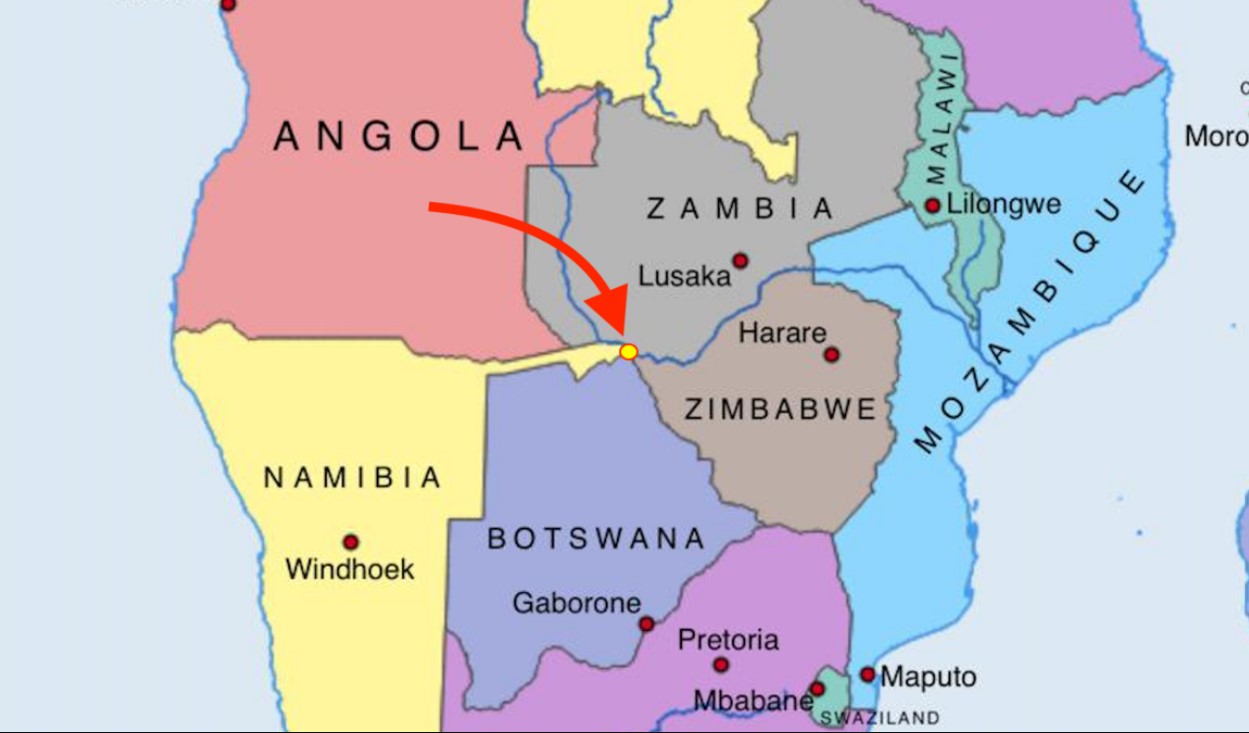

An international quadripoint is a place where four countries meet. World maps show just one: a point in southern Africa where Zambia, Zimbabwe, Botswana, and Namibia all touch, right in the middle of the Zambezi River. But they’re wrong.

Like a magic trick in reverse, the point disappears if you examine it too closely. Zoom in and the world’s only international quadripoint turns into two tripoints. The western one is where Botswana and Zambia meet Namibia. The eastern one is where they meet Zimbabwe.

The reason we’re so easily fooled – and so grievously disappointed – is that those two tripoints are separated by no more than 443 feet (135 m).

To add to the cartographic near-miss, that doesn’t even make the international border between Zambia and Botswana the shortest in the world. That distinction goes to a line just 279 feet (85 m) long, separating the tiny Spanish peninsula of Peñón de Vélez de la Gomera from the Moroccan mainland.

In short, the border here is a bit of a mess. In the 1970s, the question of whether there existed a quadripoint was a highly contentious matter between Zambia and Botswana on the one hand and the white-minority-ruled regimes of South Africa (which then occupied Namibia) and Rhodesia (as Zimbabwe was then known) on the other.

A geopolitical flashpoint no more

Should the quadripoint exist, South Africa and Rhodesia would control all cross-river traffic between Zambia and Botswana. Operating under that assumption, South Africa declared the Kazungula Ferry, which linked Zambia to Botswana, illegal. This ultimately led to an armed confrontation in 1970. A few years later, the Rhodesian Army actually sank the ferry, claiming it was serving military purposes.

With both racist regimes now consigned to the dustbin of history, the specter of a Kazungula turning into a geopolitical flashpoint has largely receded. What’s more, the Kazungula Bridge shows what excellent lemonade you can make with the lemons that geography hands you.

Cutting exactly through the “quadripoint zone,” the bridge is 3,028 feet (923 m) long and 60.7 feet (18.5 m) wide. It’s a cable-stayed construction carrying two car lanes each way, a single rail track, and pedestrian walkways on either side. It took South Korea’s Daewoo E&C six years to complete at a cost of $259 million. Financing was provided by the Zambian and Botswanan governments, the African Development Bank, the Japanese International Cooperation Agency, and the EU-Africa Infrastructure Trust Fund.

The bridge replaces a pontoon ferry which could carry just two trucks at a time. That means the busy road traffic between the Copper Belt in southern DR Congo and northern Zambia now has a viable alternate route to the South African port of Durban, one that doesn’t lead through Zimbabwe. That route is often congested at the Beitbridge border crossing into South Africa.

It was exactly for fear of losing the lucrative toll on that traffic that former Zimbabwean president Robert Mugabe withdrew from the consortium building the bridge. Zimbabwe’s “Second Republic,” under his successor Emmerson Mnangagwa, has taken the more sensible approach of requesting to rejoin and is already upgrading its roads towards the crossing.

From landlocked to “landlinked”

Either way, the bridge will ease congestion, lower the cost of doing business, and boost trade between Zambia and Botswana as well as for the wider Southern Africa Development Council (SADC), the 16-country economic and political cooperation body covering Africa’s southern third.

Africa still suffers from poor or non-existent road infrastructure. The SADC sees a well-maintained road network as key for promoting integration and development across the continent. The Kazungula Bridge is considered an essential instrument in turning Zambia and Botswana (and soon perhaps also Zimbabwe) from landlocked into “landlinked” countries.

Perhaps one day when cars and trucks can drive smoothly from Cape Town all the way up to Cairo, they’ll do so across the Kazungula Bridge.

One country that hasn’t been mentioned but is essential to the story — because there is no quadripoint without four countries — is Namibia. Located mainly on the Atlantic coast and inland desert of southwest Africa, it projects this one panhandle into southern Africa’s wet heart.

That is the Caprivi Strip, named after the German chancellor who obtained it in 1890. He wanted the then-German colony of South-West-Africa to have access to the Zambezi in the hope that it would be navigable all the way down to the Indian Ocean. It isn’t: 40 miles (70 km) east of Kazungula, the majestic Victoria Falls block off that option.

If Caprivi’s gamble had paid off, the “quadripoint zone” could now have been a bustling transit area for people and goods all across southern Africa. Thanks to the Kazungula Bridge, that vision may soon come true, if slightly differently configured.

This article was reprinted with permission of Big Think, where it was originally published.