In 1859 — on a Thursday evening, in North America — crimson columns of light began to creep across the darkened horizon. These auroras wrapped around the world, from China to Cuba, and radios and telegraph systems sputtered and stopped working en masse. Thousands of people took to the streets to see the blood red sky, some dispatching fire trucks to put out the fire that surely had set the night ablaze, while others prayed, fearing the coming of end times.

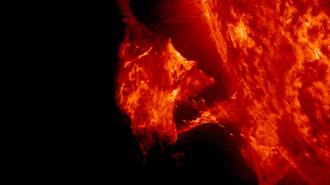

But the source was neither earthly nor divine. Now known as the Carrington Event, the planet had been struck by a super solar storm — essentially a cloud of plasma, gas, and high energy particles spewed from the sun’s surface. And such a storm could happen again. Scientists estimate about a 10% chance of a solar storm hitting the Earth within the next 10 years — or, put another way, for the optimists among us, a 90% chance that it won’t.

In either case, in today’s hyperconnected world, we’ve got a lot more technology at stake than telegraph lines. According to a 2016 study by the European Space Agency, a solar geomagnetic storm could lead to costly losses in various industries, from aviation to power systems, totaling as much as €15 billion just in Europe.

One way to minimize this damage is to keep watch on the sun’s activity using satellites, giving us time to prepare for any solar events heading our way. Current monitoring satellites, which have been in orbit for more than 20 years, provide about 15 hours of advance warning.

Now, a newly funded satellite mission by the European Space Agency (ESA), called the L5 Lagrange mission, could help us to forecast solar events up to a day or more ahead of time, says Juha-Pekka Luntama, head of ESA’s Space Weather Office.

Being able to accurately monitor solar weather events is crucial, because each type of event is unique, as are the consequences they carry.

This improved time owes to the L5 mission’s proposed position in space.

Whereas existing space weather satellites are located on a straight line between the sun and Earth, at a point called L1, the new satellite will be placed off that line, at a point called L5, which is a better vantage point for observing solar storms. You can think of it in terms of baseball, where the solar storm is the incoming pitch, Luntama says. If you’re the catcher, it’s harder to gauge the speed or position of the pitch than if you’re sitting off to the side, watching with a speed gun.

The Lagrange mission will also place the satellite 150 million kilometers away from Earth, which is 100 times farther than the satellites at the L1 position. “This is the very first time that anybody is building an operational deep space mission,” Luntama says. “Just sending the data from that distance is challenging.”

To receive an uninterrupted stream of data, space agencies need consistent access to huge antennae, at least 35 meters in diameter, at ground stations around the world, he says. While ESA’s receiver network could handle the job in theory, those dishes are needed for several other missions, which is why the agency hopes to work with others, like NASA and Japan’s JAXA, to collect the data. International collaboration often comes into play in missions where the goal is to protect the Earth, Luntama says.

Being able to accurately monitor solar weather events is crucial, because each type of event is unique, as are the consequences they carry. These solar disturbances arise from changes in the sun’s magnetic field, and they take three general forms, which can occur separately or all at once.

A solar geomagnetic storm can temporarily change the planet’s magnetic field.

The first is a solar flare. This flash from the sun’s surface can be seen from earth, if you have the right equipment and timing; it’s what amateur astronomers Richard Carrington and Richard Hodson happened to have observed before the event in 1859. Solar flares shower our atmosphere with extreme amounts of electromagnetic radiation, ionizing the upper layers. This ionization makes it hard for radio signals to get through the atmosphere, causing disruptions in things like satellite GPS receivers.

The second surprise the sun might serve up is a blast of high energy protons and electrons. While most of these energetic particles will be caught by the atmosphere, the electronics on satellites — including those monitoring the sun from the L1 position — may be damaged, temporarily or for good depending on the event. These pesky particles can also affect solar panels, degrading the panels over time.

But the event that could have the biggest impact on our day to day lives is a coronal mass ejection (CME). In this case, an explosion on the surface of the sun ejects a chunk of the sun’s plasma out into the void at speeds up to 3,000 km/s.

This cloud — a solar geomagnetic storm, can span hundreds of millions of kilometers wide and, upon collision with Earth, can even temporarily change the planet’s magnetic field.

To be clear, human life on the ground, as well as our dear personal electronic devices, like phones and laptops, are never in any danger from solar storms, Luntama says (adding that he gets this question a lot).

One effect a storm could have is on high frequency radio communications used in aviation. And while disruptions might hamper flight operations, the industry has redundancies in place to carry on safely if just more slowly, Luntama says, suggesting that the conditions may be like what you might expect in bad weather conditions.

“There will be delays, there might be cancellations because the airports can’t run the take-offs and landings as efficiently as they do normally,” he says.

Another issue that’s minor but needs to be monitored is increased radiation exposure for astronauts and flight crews flying close to the poles, where radiation can seep into the upper atmosphere. The amount of radiation exposure a regular commercial flight passenger might experience during a solar storm isn’t dangerous, but a crew member serving multiple flights may need to be careful that they don’t exceed their recommended yearly radiation levels.

The biggest threat solar storms pose is to the power grid. A geomagnetic storm can deliver an extra jolt of current straight into power systems, overloading the grid and knocking out crucial house-sized transformers, which are expensive and difficult to replace.

The biggest threat solar storms pose is to the power grid. A geomagnetic storm can deliver an extra jolt of current straight into power systems

With advance notice, Luntama suggests that power companies could lower the grids’ loads or turn them off completely, as a costly but protective measure. Here’s where that extra half a day of warning time could be crucial. You can’t just turn off entire power grids by flipping a switch, Luntama says. These systems must be carefully ramped down over the course of days.

In case of any emergency, whether it’s a hurricane or solar storm, utility companies have business continuity plans, says Eileen Unger of Emergency Preparedness Partnerships, a New Jersey based company that helps businesses write and practice such plans.

These plans prepare for the loss of things like computer systems and communications, including how to revert to paper records or how many employees are needed to update customers in person. In the worst-case scenario, if all methods of communications were down, Unger says, companies might designate a location for employees to meet and receive further instructions.

Luntama says, for individual citizens, the best thing you can do to prepare for solar storms is to understand their impact and not to panic.

Ultimately, the key to minimizing the damage caused by solar storms is long-term planning, Luntama says, and ensuring that governments around the world are investing in monitoring capabilities. Solar storms are one of the few threats where the entire planet is vulnerable, he says. “As mankind, we need to take this seriously.”