If you’ve ever played one of those “spot the difference between these two photos” games, you have something in common with NASA scientists.

To identify newly formed craters on Mars, they’ll spend about 40 minutes analyzing a single photo of the Martian surface taken by the Context Camera on NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), looking for a dark patch that wasn’t in earlier photos of the same location.

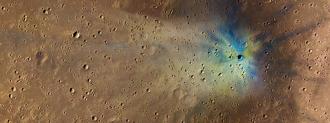

If a scientist spots the signs of a crater in one of those images, it then has to be confirmed using a higher-resolution photograph taken by another MRO instrument: the High-Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE).

This method of spotting new craters on Mars makes it easy to determine an approximate date for when each formed — if a crater wasn’t in a photo from April 2016 but is in one from June 2018, for example, the scientists know it must have formed sometime between those two dates.

By studying the characteristics of the craters whose ages they do know, the scientists can then estimate the ages of older ones. This information can improve their understanding of Mars’ history and help with the planning of new missions to the Red Planet.

The problem: this is incredibly time-consuming.

The MRO has been taking photos of the Red Planet’s surface for 15 years now, and in that time, it has snapped 112,000 lower-resolution images, with each covering hundreds of miles of the Martian surface.

To free scientists from the burden of manually analyzing all those photos, researchers trained an algorithm to scan the same images for signs of new craters on Mars — and it only needs about five seconds per picture.

Fresh Craters on Mars

To train their image-analyzing AI to spot new craters on Mars, the researchers started by feeding it nearly 7,000 images from the Context Camera. Some featured fresh craters confirmed by HiRISE photos, and others didn’t.

After training, the next step was letting the algorithm analyze all of the Context Camera images.

This is just beginning. We’re looking forward to finding a lot more.

Ingrid Daubar

To speed it up, the researchers ran the AI on a supercomputer cluster at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).

“It wouldn’t be possible to process over 112,000 images in a reasonable amount of time without distributing the work across many computers,” JPL computer scientist Gary Doran said in October. “The strategy is to split the problem into smaller pieces that can be solved in parallel.”

With the power of all those computers combined, the AI could scan an image in an average of just five seconds. If it flagged something that looked like a fresh crater, NASA scientists could then check it out themselves using HiRISE.

Scanning the Martian Surface

In October, NASA confirmed that the AI had discovered its first fresh craters on Mars, and to date, it’s helped scientists spot dozens of new impacts in the Context Camera images.

“The data was there all the time,” JPL computer scientist Kiri Wagstaf told Wired. “It’s just that we hadn’t seen it ourselves.”

In the future, the AI might help scientists identify more craters on Mars — potentially within weeks of their formation — or even craters on other planets.

“The possibility of using machine learning to really delve into large data sets and find things that we otherwise wouldn’t have found is really exciting,” Ingrid Daubar, a planetary scientist who helped create the AI, told Wired.

“This is just beginning,” she added. “We’re looking forward to finding a lot more.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].