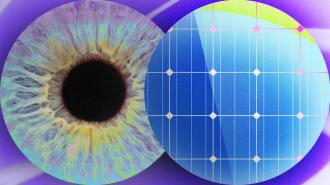

Australian researchers are developing tiny implantable solar cells that could be inserted into the eye to help restore vision — and they’re using an unusual material to do it.

The challenge: It’s the job of nerve cells called “photoreceptors” to convert the light that enters our retinas into electrical signals that can then be sent down the optic nerve to our brain for processing.

Photoreceptors are often damaged or destroyed by age, disease, or injury, though, leading to vision problems — age-related macular degeneration, the top cause of vision loss in seniors, is one example of an eye disease related to damaged photoreceptors.

Having wires delivering power into the eye is, pretty obviously, not an ideal solution.

Implantable solar cells: It may be possible to use eye implants to create the electrical signals needed for sight, bypassing eye damage. Scientists are already trialing such tech, but figuring out the best way to power the systems is an important part of that research.

Having wires delivering power into the eye is, pretty obviously, not an ideal solution, so some are exploring the use of implantable solar cells — light could enter the eye, hit a solar cell implanted in the retina, and be converted into the electrical signals needed for vision.

What’s new? The solar cells used for these experiments are often made of the same material as the cells in solar farms — silicon — but Udo Roemer, an engineer specializing in photovoltaics at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) is taking a different approach, using gallium arsenide for his research.

“We’re looking at how we can stack them, one on top of the other.”

Udo Roemer

This semiconducting material is slightly more expensive than silicon, but it’s easier to work with and still commonly used in the solar power industry due to its high efficiency.

“In order to stimulate neurons, you need a higher voltage than what you get from one solar cell,” said Roemer. “If you imagine photoreceptors being pixels, then we really need three solar cells to create enough voltage to send to the brain.”

“So we’re looking at how we can stack them, one on top of the other, to achieve this,” he continued. “With silicon this would have been difficult; that’s why we swapped to gallium arsenide where it’s much easier.”

“Sunlight alone may not be strong enough to work with these solar cells.”

Udo Roemer

Solar boost: Though the implantable solar cells would, presumably, be far more convenient than having wires coming out of your eyes, Roemer cautions that the tech might need an extra boost from external hardware in order to help restore vision.

“One thing to note is that even with the efficiencies of stacked solar cells, sunlight alone may not be strong enough to work with these solar cells implanted in the retina,” he said.

“People may have to wear some sort of goggles or smart glasses that work in tandem with the solar cells that are able to amplify the sun signal into the required intensity needed to reliably stimulate neurons in the eye,” he continued.

Looking ahead: So far, Roemer’s team has managed to stack two solar cells in an area of about 1 cm2. Their goal is to shrink it down and then focus on adding a third layer.

There’s still a lot of work to do before the tech could be used to help restore vision in people, but if preclinical trials go well, the team’s goal will be to get the cells down to 2 mm2 — about three times as big as the tip of a ballpoint pen — for testing in people.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].