A Chinese rover has found evidence that there was liquid water on Mars far more recently than we thought — a discovery that could affect plans to one day colonize the Red Planet.

Liquid water on Mars: Based on past research, scientists believed there was liquid water on Mars up until about 3 billion years ago — the point at which the planet’s dry “Amazonian” epoch began and the geological era before it (the “Hesperian” epoch) ended.

“Hydrated minerals and ground ice can be used as the important water resource on Mars.”

Yang Liu

Understanding the history of liquid water on Mars can help us predict how much water remains on the Red Planet, in the form of ice or hydrated minerals. We might then be able to use that existing water on Mars to support crewed missions.

“One of the most important resources for human explorers is water,” lead study author Yang Liu from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) told CNN. “Hydrated minerals, which contain structural water, and ground ice can be used as the important water resource on Mars.”

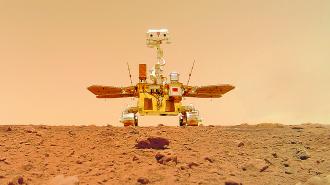

What’s new? After landing on Mars in May 2021, China’s Zhurong rover began collecting data on soil samples. When researchers from CAS and the University of Copenhagen analyzed some of that data, they found evidence of water in samples that were just 700 million years old.

This suggests that the area being explored by the Zhurong rover — Mars’ Utopia Planitia, a plain in a huge impact crater — was home to a “substantial” amount of liquid water at a time when we thought Mars’ surface was already dried up.

“One of the major things we’ll have to find out … is how extensive these ‘young’ water-bearing minerals are.”

Eva Scheller

Looking ahead: The data used for this study was collected during Zhurong’s first 92 Martian days (sols) of exploration. The rover has now spent 350 sols on Mars, traveling more than a mile across its surface.

The whole time it’s been collecting data that could further inform our understanding of liquid water on Mars.

“One of the major things we’ll have to find out and that I look forward to seeing from the Zhurong rover is how extensive these ‘young’ water-bearing minerals are,” Eva Scheller, a planetary scientist at CalTech, who wasn’t involved in the study, told Space. “Are they common or uncommon in these ‘young’ rocks?”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].