NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has directly observed a planet outside our solar system for the first time — ushering in a new era of exoplanet research.

“There are many more images of exoplanets to come that will shape our overall understanding of their physics, chemistry, and formation,” said Aarynn Carter, a UC Santa Cruz researcher who led the analysis of the JWST images. “We may even discover previously unknown planets, too.”

The challenge: For thousands of years, the only planets we knew about were the ones orbiting our sun, but that changed in 1992 with the discovery of the first “exoplanets.”

Our view of most exoplanets is obscured by their star’s light.

Since then, we’ve identified more than 5,000 exoplanets, but nearly all of them have been discovered through indirect observation — astronomers noticed regular dips in a star’s brightness, for example, and were able to infer that an exoplanet was in its orbit.

Direct observations can reveal details we can’t get through indirect methods, but our view of most exoplanets is obscured by their star’s light. As a result, fewer than 30 exoplanets have been directly observed, and they’re mostly young gas giants distantly orbiting their stars.

First look: Specialized telescope attachments called “coronagraphs” can block out the direct light from a star to aid observations of the objects around it.

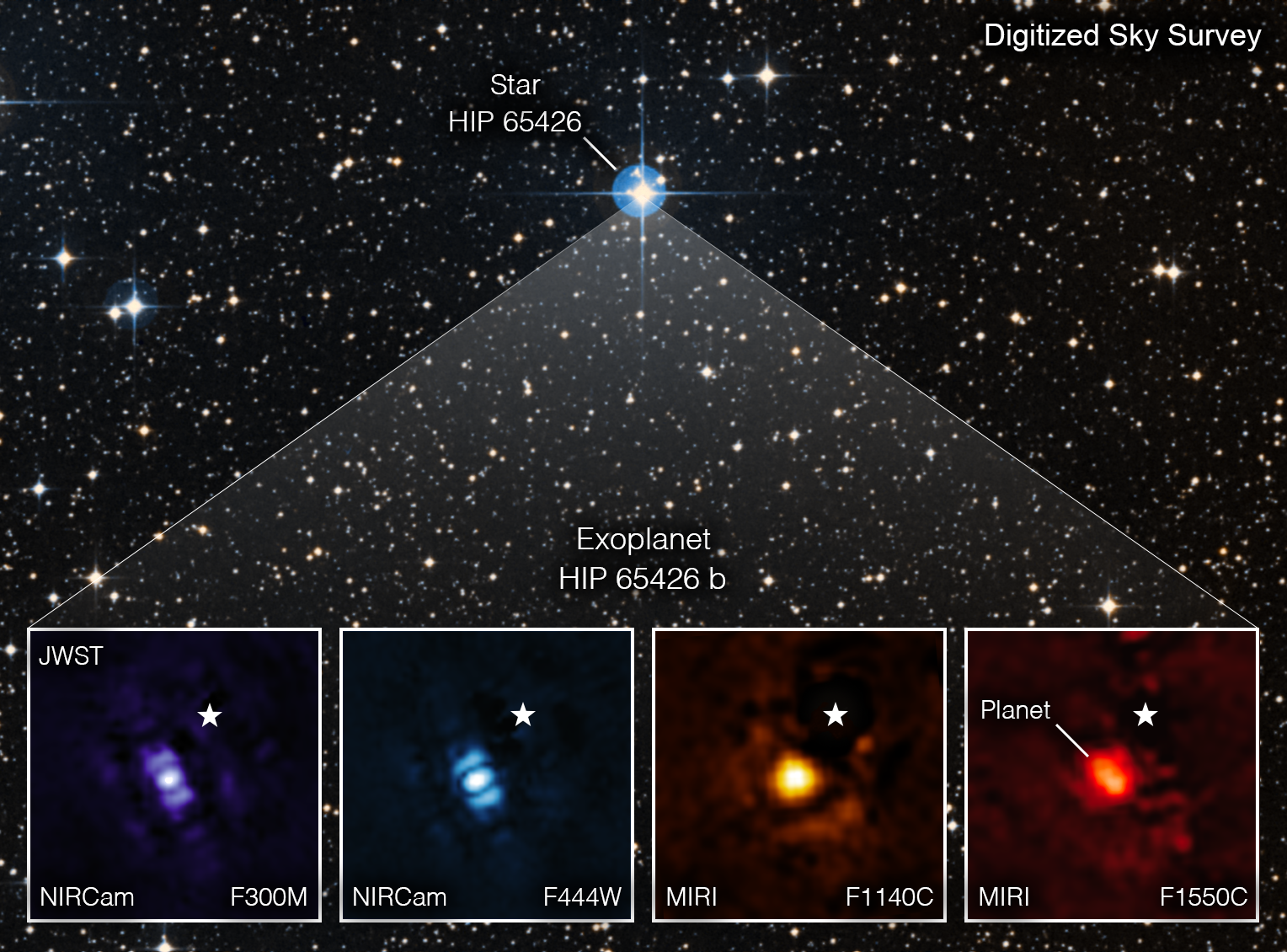

JWST has coronagraphs on two of its four scientific instruments — Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) and Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) — and they’ve now been used to produce the telescope’s first direct image of an exoplanet: HIP 65426 b.

“With careful image processing, I was able to remove [the star’s] light and uncover the planet.”

Aarynn Carter

HIP 65426 b is a gas giant with a radius about 1.5 times that of Jupiter. It’s 385 light-years away from Earth and only 15-20 million years old — a relative baby compared to our 4.5 billion-years-old planet.

HIP 65426 b was discovered using a ground-based telescope in 2017, but JWST’s observations are expected to reveal new details on the exoplanet, such as a more exact measurement of its mass — the researchers are now preparing a paper for submission to a peer-reviewed journal.

“Obtaining this image felt like digging for space treasure,” said Carter. “At first all I could see was light from the star, but with careful image processing I was able to remove that light and uncover the planet.”

Looking ahead: In the future, we can expect to see JWST used to directly image many more exoplanets, and based on the precision of these first observations, it might even be able to image smaller, fainter exoplanets than was previously possible.

“The telescope is more sensitive than we expected, but it is also very stable,” Carter told LiveScience. “Previously we’ve been limited to detections of super-Jupiters, but now we have the potential to image objects similar to Uranus and Neptune for the right targets.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].