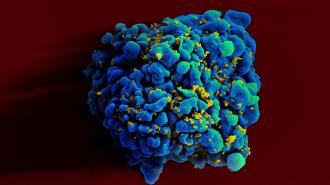

For the first time, a woman has been cured of HIV through a stem cell transplant — and her treatment suggests a way to help more people free their bodies of the virus.

The background: In 2007, an HIV-positive man named Timothy Ray Brown got a transplant of bone marrow — the stem cell-containing tissue inside your bones — to treat his leukemia.

The bone marrow came from a donor with a rare genetic mutation that blocks HIV, and after the transplant, Brown was functionally cured of HIV.

Since then, another man has been cured through the same treatment, and a third has gone three years with his HIV in remission.

The challenge: Treating every HIV patient with a bone marrow transplant is not a viable solution to the AIDS crisis.

First, the bone marrow needed for the transplants is not widely available — to date, researchers have only identified the HIV-preventing genetic mutation in about 20,000 donors.

The bone marrow came from a donor with a rare genetic mutation that blocks HIV.

A donor must also be a close biological match for the recipient. Matches are more likely between people of similar ethnicity, and because most bone marrow donors are of European descent, people of other ethnicities have a particularly tough time finding a match.

A bone marrow transplant is also a highly invasive, risky procedure — Brown nearly died after his. Given that HIV can now be managed with medication, it’s only considered for patients who must have the transplant to treat something else, such as cancer.

What’s new? The UCLA team has now reportedly cured a mixed-race woman with leukemia of HIV using a different method.

Instead of transplanting bone marrow, the doctors transplanted stem cells from donated umbilical cord blood from an infant with the HIV-blocking mutation. Cord blood is more available than bone marrow, safer to transplant, and doesn’t have to match a recipient as closely.

At the same time, the woman also received a donation of partially matched stem cells from a close relative (who doesn’t have the desirable genetic mutation).

Umbilical cord blood is more available than bone marrow, safer to transplant, and doesn’t have to match a recipient as closely.

“The transplant from the relative is like a bridge that got her through to the point of the cord blood being able to take over,” Marshall Glesby, a member of the research team, told the New York Times.

The woman had a much easier time recovering from the transplant, which took place in 2017, than the men cured of HIV with a bone marrow transplant. She was able to leave the hospital just 17 days after the procedure — and today, she has no detectable signs of HIV in her body.

We could soon see additional patients cured of HIV in this way, too. The woman was part of UCLA’s IMPAACT study, which plans to use transplants of mutation-carrying umbilical cord blood to treat 25 HIV-positive people with cancer and other diseases.

The big picture: Knowing that umbilical cord blood can also cure HIV is huge. Doctors may now be able to use it to treat people who wouldn’t have been able to find a matching bone marrow donor with the protective mutation.

Still, this kind of cure is likely out of reach for the vast majority of people with HIV.

Most attempts to cure HIV with bone marrow transplants have failed, and even if this transplant went easier than the two men cured of HIV, transplants using umbilical cord blood are still risky and only suitable for patients that need them to treat something else.

The patient was able to leave the hospital just 17 days after the procedure.

Doctors could learn something from the success of these transplants that leads to a broader cure for HIV, though.

“Taken together, these three cases of a cure post stem cell transplant all help in teasing out the various components of the transplant that were absolutely key to a cure,” Sharon Lewin, President-Elect of the International AIDS Society, said in a statement.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].