In 1992, the US government intruded into Americans’ showers, mandating that shower heads sold in the US permit water flow of no more than 2.5 gallons per minute. The move, though decried by many, was in reality a well-meaning attempt to reduce freshwater consumption and help consumers save on water heating bills. Before the policy change, most shower heads sprayed up to five gallons of water per minute. After the low-flow mandate, an eight-minute shower would thus theoretically use 20 gallons of water instead of 40.

Today, twelve states have shower head regulations more stringent than federal mandates. Heads sold in California, Hawaii, New York, Oregon, and Washington have their flow rates capped at 1.8 gallons per minute.

According to estimates, the average shower in America now lasts 8.2 minutes and uses just over 17 gallons of water. In developed countries, showers account for about a fifth of household water use.

As a changing climate threatens many parts of the world with drought and water supply instability, many countries might be looking to cut household water use by further restricting water flow from shower heads. But a new study out of the UK, yet to be peer-reviewed, might complicate this approach.

In a fascinating twist, the researchers found a striking relationship between a shower head’s water pressure and overall water consumption.

Professor Ian Walker, an environmental psychologist at the University of Swansea; James Daly, Sustainability Manager at the University of Bristol; and Dr. Pablo Pereira-Doel, a Sustainability Fellow at the University of Surrey, teamed up to install water sensors in 290 showers around the University of Surrey campus. These sensors tracked the length of showers. Some also displayed timers to students showing how long they had been showering.

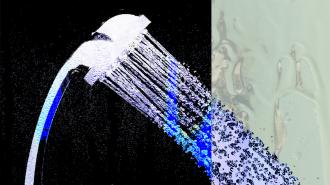

During installation, the researchers measured the water pressure and flow rate of each shower head. Water pressure, measured in pounds per square inch (psi), is the amount of force exerted on water to make it move. Flow rate, measured in gallons or liters per minute, is the amount of water coming out of a faucet over a certain time.

The researchers then monitored shower lengths at the 290 locations for 39 weeks. They ended up with data on 86,000 individual showers.

“We knew exactly how long the water ran in each showering event, and we knew what the water flow rate was in each shower, so we could reliably estimate how much water was consumed each time somebody showered,” Walker explained on X.

In a fascinating twist, they found a striking relationship between a shower head’s water pressure and overall water consumption. It turns out that people took shorter showers when the water pressure was greater. For shower heads “dribbling” water at a paltry 16 to 32 psi, showerers used an average of 16 gallons (60.6L) of water. With a more forceful spray of 32 to 49 psi, people used 12.8 gallons (48.3L). When water blasted at 49 to 65 psi, people got done with just 6.3 gallons (24.2L).

It’s possible that higher water pressures allowed users to clean themselves more efficiently, removing soap and shampoo more quickly. Walker also speculated that higher pressure showers might simply feel more satisfying.

“It suggests that people turn the shower off when they have achieved a desired sensation, not just when they have completed a certain set of actions,” he wrote.

The study’s findings could have intriguing policy implications. Since reducing water flow can lower water pressure, mandates that further restrict flow rates from shower heads could backfire, driving people to take longer showers and thus consume more water. Specially designed shower heads with narrower openings can preserve pressure, but only to a degree.

Still, the researchers believe that there’s room to lower flow before water pressure is reduced to the point where people take longer showers.

“There is likely to be an inflection point where lowering the flow will no longer be beneficial,” Daly told Freethink. “This is something we’d like to investigate. However we didn’t reach that point & had showers down to a little below 5L/min [1.3 gallons/min].”

“This is hot water, so potentially massive carbon savings.”

Ian Walker

The study also found that in the showers that they had modified to show the timer, people used relatively less water over time.

“Putting the two effects together, we saw average water consumption shift from nearly 61 litres/shower (low pressure, no timer) to under 17 litres/shower (high pressure, timer),” Walker noted on X. “Remember, this is hot water, so potentially massive carbon savings.”

There are some caveats: these were students, and they do appear to have different showering habits than the general UK population — their showers averaged just 6.7 minutes, over four minutes shorter than the national average. The researchers also measured water pressure just behind the shower head, rather than coming out of it. So variances in shower height and shower head could alter the sensation of water pressure for users.

“This eye-opening research shows manufacturers and policymakers that they need to beware of the unintended consequences of well-meaning efforts to perpetually lower flow without considering other factors,” Tom Reynolds, Chief Executive at Bathroom Manufacturers Association, said in a statement. The industry has long opposed restrictions on shower head flow.

Walker said on X on that his group next plans to study the effect of other ways to boost the apparent pressure of showers, without increasing the water flow rate.

The UK, the western United States, and numerous other locations around the world are projected to face water supply shortfalls by mid-century, which makes research on real-world water consumption particularly important.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].