Since the 1980s, an American man named Dennis Hope has been selling plots of land on the moon. As of 2013, Hope claimed to have sold 611 million acres of lunar real estate, at a pre-tax price of $19.95 per acre. His argument–dismissed by space law experts many times over the years–is that international treaties prohibiting any country from owning the moon don’t apply to individuals. So Hope made his claim and then started selling deeds.

Profiles of Hope make for entertaining reading. But they also raise an interesting question: If he doesn’t own the moon, who does? And if no one does, who gets to decide what happens there?

“We’re nowhere near being ready to live on the moon,” you might be thinking. And you would be right! But we’re probably very close to being ready to extract resources from the moon, which means we need rules.

What are the rules of outer space right now?

In 1967, the United Nations passed the Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies; today we refer to it as just the Outer Space Treaty. The agreement has been signed and ratified by 104 countries, and it was mostly intended to keep the United States and the Soviet Union from turning outer space into a battlefield.

As such, the treaty has little to say about who can make money off natural resources in outer space. In fact, there’s only one paragraph that speaks to that concern. It says, “Outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.”

So, no one can own anything in space?

It depends on who you ask. The language in the Outer Space Treaty says no country can exclusively claim any celestial body, but it doesn’t explicitly prohibit countries or commercial actors from selling things–like minerals–obtained in space. It also doesn’t say they can.

Enter the U.S. Government: In 2015, both houses of Congress passed, and President Barack Obama signed, the U.S. Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act. The law covers a number of issues, but the most buzzworthy provision is this paragraph:

“A United States citizen engaged in commercial recovery of an asteroid resource or a space resource under this chapter shall be entitled to any asteroid resource or space resource obtained, including to possess, own, transport, use, and sell the asteroid resource or space resource obtained in accordance with applicable law, including the international obligations of the United States.”

In effect, the U.S. declared that while Americans can’t claim ownership of planetary bodies, they can keep (and sell) what they find on those bodies.

In effect, the U.S. declared that while Americans can’t claim ownership of planetary bodies, they can keep (and sell) what they find on those bodies.

What happens if other countries don’t want U.S. companies mining the moon?

That’s the big question space law advocates are mulling over. The Outer Space Treaty was an easy pass largely because the world was more interested in preventing the Cold War from leaking into space than establishing rules for minerals rights. Humans just weren’t ready for space mining in 1967, but the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. were ready for war.

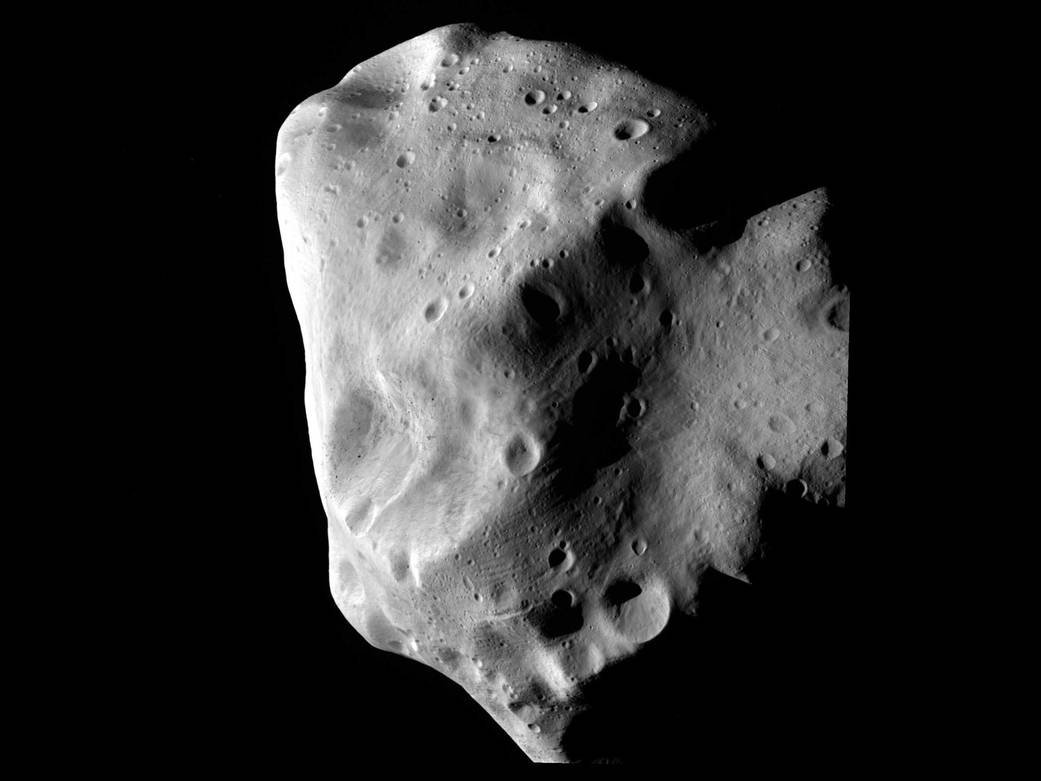

But U.S.-based space companies are optimistic that the law won’t lead to international umbrage. For one thing, there’s a lot of moon to go around, and more than 150 million asteroids in the inner solar system. That means the number of places from whence we can extract resources vastly outnumber our species’ collective ability to extract them.

At the same time, the U.S. Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act doesn’t prohibit other countries from passing their own resource laws, and there’s no reason to think the U.S. would object if they did. Bob Richards, the CEO of lunar mining company Moon Express, thinks the act is a first step to establish normal, peaceful mining policies that every country could adopt.

“The more that the world agrees that this is OK, the more that we have a chance to be a mature and responsible spacefaring species,” Richards told Space News in 2015. “It really is a chance for us, as humans, to find a way to conquer a new frontier without conquering each other. It’s a new opportunity for us to try to get things right.”

What about colonization? And the rest of space?

Good questions, but the answers are far less clear. The Outer Space Treaty says no country can claim sovereignty, which makes colonizing Mars a murky proposition (and not just because we don’t currently have a viable way to do it).

One proposal is likely to make potential Mars settlers a bit nervous: Let the settlers figure it out on their own.

One proposal is likely to make potential Mars settlers a bit nervous: Let the settlers figure it out on their own.

“Rather than extend the ideas of the parent nation, corporation, or global order, colonists arriving on a liberated Mars would relinquish their former status as earthlings and embrace a new planetary citizenship as martians,” Jacob Haqq-Misra proposed in the Boston Globe last year.

Such an approach would require Mars settlers to “fend for themselves to develop their own systems of conflict resolution, governance, currency, education, art, music, and spirituality — without depending upon any of the legal protections of Earth.”

It would also be a tougher sell to the Earth’s governments, which currently operate under the mutual understanding that countries are responsible for what their citizens do in space.

It sounds like there are no solid answers to any of these questions

You are not wrong. But there is a general belief among space advocates that settling the solar system should be done with an eye toward peace and cooperation.

“As a civilized species, we should think about how not to do what we did in the 14th and 15th centuries,” Dr. Ram S. Jakhu, director of the Institute of Air and Space Law at McGill University told me on a recent phone call.

“Europe went to new places, killed people, and destroyed the environment. But that was in keeping with what our species did 500 years ago. Are we more civilized now? We must have a different thinking for exploring space than we did for exploring our own planet.”

Fingers crossed.