Scientists have discovered a CRISPR-like system in animals that can be programmed to edit human cells — adding another gene-editing system to our growing toolbox.

The challenge: About a decade ago, scientists discovered that they could use CRISPR-Cas9 — a natural defense system found in some bacteria — to make precise edits in the DNA of plants, animals, and other complex organisms.

CRISPR is incredibly useful, but has several limitations.

Since then, the gene-editing system has been used to cure diseases, improve crops, and more. But a limitation of the tech is its propensity for “collateral activity,” degrading parts of the genome near its target while making edits.

CRISPR-Cas9 is also rather large, which has made delivering the system into human cells a challenge — the adeno-associated viral vectors commonly used to deliver other gene therapies, for example, can’t hold a whole CRISPR-Cas9 system.

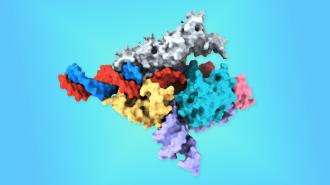

What’s new? Feng Zhang — an early pioneer of CRISPR as a gene-editing system — has now led the discovery of a new CRISPR-like system, based on an enzyme called Fanzor.

The Fanzor gene-editing system is more compact and precise.

Unlike CRISPR, which has only been found in prokaryotes (organisms whose cells don’t contain a nucleus), this one was discovered in several eukaryotic species (organisms whose cells do have a nucleus), including species of plants and animals.

Not only is this gene-editing system more compact than CRISPR-Cas9, suggesting that it might be easier to deliver into human cells, a version of Fanzor sourced from fungi didn’t show any signs of collateral activity when tested on human cells in the lab.

Fanzors from fungi, algae, and even a clam were used to edit human cells.

The discovery: In 2021, Zhang’s team discovered a class of ancient gene-editing systems in prokaryotes, dubbed OMEGAs, that they believe to be the forerunners of CRISPR. At the time, they noted that the enzymes involved in OMEGAs were similar to the Fanzor enzymes found in eukaryotes.

“These OMEGA systems are more ancestral to CRISPR, and they are among the most abundant proteins on the planet, so it makes sense that they have been able to hop back and forth between prokaryotes and eukaryotes,” said co-first author Makoto Saito.

The researchers suspected that Fanzor enzymes could be programmed to edit DNA, like the Cas enzymes in a CRISPR system, and in their new study, published in Nature, they proved that ability, using Fanzors from fungi, algae, and even a clam to make insertions and deletions in human cells.

“Nature is amazing. There’s so much diversity.”

Feng Zhang

Looking ahead: Initially, the Fanzor-based gene-editing system was only successful at making its edits about 12% of the time, but by introducing precise mutations into the enzymes, Zhang’s team was able to increase the efficiency to 18%.

The efficiency would need to be improved further before it could be used for medical therapies, but even if that isn’t possible, the discovery of one CRISPR-like system in animals hints at the existence of others.

“Nature is amazing. There’s so much diversity,” said Zhang. “There are probably more RNA-programmable systems out there, and we’re continuing to explore and will hopefully discover more.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.