For the first time ever, deep brain stimulation has been shown to help people regain cognitive abilities they’d lost following a traumatic brain injury (TBI).

“These participants had experienced brain injury years to decades before, and it was thought that whatever recovery process was possible had already played out, so we were surprised and pleased to see how much they improved,” said study co-leader Nicholas Schiff, a professor of neuroscience at Cornell University.

The challenge: A TBI occurs when you hit or jolt your head so hard that your brain moves inside your skull. This can lead to a loss of consciousness and cause damage that affects brain function.

While the symptoms of a mild TBI, such as a concussion, are usually temporary, people with moderate to severe TBIs can experience permanent problems with cognition, emotion, and movement that can prevent them from being able to work or live independently.

“I couldn’t remember anything,” said Gina Arata, a Californian who suffered a TBI in 2001. “My left foot dropped, so I’d trip over things all the time. I was always in car accidents. And I had no filter — I’d get pissed off really easily.”

What’s new? In 2018, Arata joined CENTURY-S, a small trial in which researchers electrically stimulated a precise brain region in people who’d experienced a moderate to severe TBI. The hope was that this would alleviate their symptoms and improve their quality of life.

The results, now published in Nature Medicine, were remarkable.

“I don’t trip anymore. I can remember how much money is in my bank account.”

Gina Arata

Three months after the devices were implanted, the five people who completed the trial performed 15-55% better on a test of mental processing speed. (A sixth person withdrew from the trial due to a minor post-op scalp infection that required removal of the stimulation device.) The trial’s goal was at least a 10% improvement.

Interviews with the participants and their families also revealed improvements in mood, motivation, self-control, stamina, and more.

“Since the implant I haven’t had any speeding tickets,” said Arata. “I don’t trip anymore. I can remember how much money is in my bank account. I wasn’t able to read, but after the implant I bought a book, Where the Crawdads Sing, and loved it and remembered it. And I don’t have that quick temper.”

The idea: Because people who experience a moderate to severe TBI are typically able to recover much of their cognitive function after regaining consciousness, the researchers suspected that the brain circuits controlling the abilities were mostly preserved.

“In these patients, those pathways are largely intact, but everything has been down-regulated,” said co-senior author Jaimie Henderson, a professor of neurosurgery at Stanford University. “It’s as if the lights had been dimmed and there just wasn’t enough electricity to turn them back up.”

“Our idea has been to overdrive this part of the thalamus to restore brain function.”

Nicholas Schiff

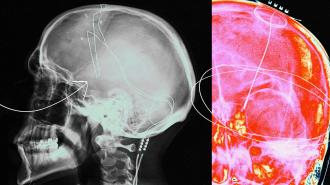

Research determined that a part of the brain’s thalamus, called the “central lateral nucleus,” was a hub for many of the pathways affected by a TBI, providing them with energy, so that’s where they implanted their electrodes.

“Basically, our idea has been to overdrive this part of the thalamus to restore brain function, much as a cardiac pacemaker works to restore heart function,” said Schiff.

How it works: Using a combination of brain imaging and algorithms, the researchers predicted exactly where to place the electrodes in each participant to maximize the activation of the target circuits while minimizing any effects on other parts of the brain.

They then ran wires from the electrodes under the patient’s skin to a battery pack and controller implanted in their chest.

After fine-tuning the stimulation, they began administering it for 12 hours a day. From the perspective of the patients, the improvement was so dramatic that two of the five participants declined to participate in a blinded withdrawal phase, as that meant there’d be a chance their device would be turned off.

“This is a pioneering moment.”

Nicholas Schiff

Looking ahead: While the results of the trial were remarkable, the deep brain stimulation didn’t “cure” any of the patients — they’re more like their pre-injury selves, but still living with challenges caused by their TBI.

Still, this is the first time deep brain stimulation has been shown to lead to improvements for people with lasting impairments due to TBI. The team is now planning a phase 2 trial that will test the therapy in 25 to 50 people.

“This is a pioneering moment,” said Schiff. “Our goal now is to try to take the systematic steps to make this a therapy. This is enough of a signal for us to make every effort.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.