A new targeted therapy that killed more than 70 types of cancer in preclinical tests — without harming healthy cells — is now being trialed in people.

The challenge: A targeted therapy for cancer focuses on a specific gene or protein that cancer cells need to grow, divide, and spread. While these can be highly effective treatments, cancer often evolves to resist them.

In theory, a protein named PCNA (“proliferating cell nuclear antigen”) would be an ideal target for a cancer therapy — all growing solid tumors rely on a mutated form of PCNA to repair and replicate their cells.

Unfortunately, PCNA was long thought to be “undruggable,” meaning there was no way to effectively target the protein with a treatment.

A new targeted therapy: Researchers at City of Hope appear to have overcome the challenge of targeting the mutated form of PCNA with a new drug, called AOH1996.

“City of Hope was able to develop an investigational medicine for a challenging protein target.”

Long Gu

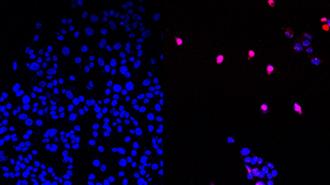

In a new study, they detail how the drug killed more than 70 types of cancer in lab tests and 3 types (neuroblastoma, breast cancer, and small-cell lung cancer) in tests on mice. It didn’t show any signs of toxicity toward healthy cells when administered to mice and dogs, either — even when they were given 6 times the effective dose.

“No one has ever targeted PCNA as a therapeutic because it was viewed as ‘undruggable,’ but clearly City of Hope was able to develop an investigational medicine for a challenging protein target,” said lead author Long Gu.

How it works: When cells divide, the mechanisms for duplicating the cell’s DNA and those for expressing its genes sometimes collide with one another.

These events are called “transcription replication conflicts” (TRCs), and they can lead to genome instability and DNA damage. To avoid that, our cells have mechanisms for resolving these conflicts.

“We need new therapeutics with new mechanisms of action…AOH1996 is just that kind of new therapy.”

Daniel Von Hoff

City of Hope’s targeted therapy interferes with this resolution process in cancer cells — which have been shown to experience more TRCs than healthy cells — by enhancing an interaction between the mutated form of PCNA and an enzyme called RPB1.

“As far as we are aware, our results are the first to demonstrate that PCNA and RBP1 interaction creates a cancer-selective vulnerability, which can be readily observed in preclinical models,” the researchers write in their study.

Looking ahead: A phase 1 clinical trial of AOH1996 launched in October 2022. City of Hope’s plan is to enroll eight people with treatment-resistant solid tumors in the trial, with each taking the targeted therapy, delivered as a pill, twice a day for 28 days.

If their disease hasn’t stopped progressing at the end of the 28 days, another 28-day cycle begins with a larger dosage. The plan is to repeat this until the cancer stops growing or the treatment proves too toxic to continue.

“Since many patients’ cancers become resistant to our standard therapies, we need new therapeutics with new mechanisms of action…AOH1996 is just that kind of new therapy,” said study co-author Daniel Von Hoff.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.