City of Hope researchers have discovered that a type of immune cell linked to allergies can kill a variety of cancer cells — opening the door to an entirely new immunotherapy.

The challenge: Because cancer starts out as your own healthy cells, it can fly under the immune system’s radar more easily than viruses or bacteria.

Some immune cells can recognize and attack cancer cells — natural killer cells and T cells, for example — but they can be overwhelmed by the speed at which the cancer spreads. In some cases, cancer cells even trick immune cells into helping them grow.

Immunotherapy 101: With a little help from doctors, immune cells can become super-charged weapons in the fight against cancer — a treatment called CAR-T cell therapy, for example, engineers a patient’s T cells so that they target the cancer.

Such treatments are known as “immunotherapies,” and researchers at City of Hope have discovered that another immune cell, called a “human type 2 innate lymphoid cell” (ILC2), could be the basis for an entirely new immunotherapy.

“The City of Hope team has identified human ILC2 cells as a new member of the cell family capable of directly killing all types of cancers, including blood cancers and solid tumors,” said senior author Jianhua Yu.

“It was a real surprise in the field to find that human ILC2s function as direct cancer killers while their mouse counterparts do not.”

Michael Caligiuri

How it works: ILC2s were discovered only in 2010 and are involved in the immune response to certain parasites and allergens. Researchers have studied their potential as a new immunotherapy for cancer before, using mouse ILC2s, but they came up short.

The City of Hope team took a different approach, using human ILC2s for their study, and this time, they saw that the immune cells could kill cancer.

“Typically, mice are reliable models for predicting human immunity, so it was a real surprise in the field to find that human ILC2s function as direct cancer killers while their mouse counterparts do not,” said co-senior author Michael Caligiuri. “It is remarkable that something has evolved so distinctly in going from mouse to human.”

Because these immune cells are rare in the body, the City of Hope team developed a platform that allowed them to multiply ILC2s extracted from a blood sample. The platform is fast, too — in just four weeks, they were able to create 2,000 times the original number of ILC2s.

When they injected the cells into mouse models of several types of cancer, including leukemia, lung cancer, and glioblastoma (a deadly brain cancer), the cells killed the cancer.

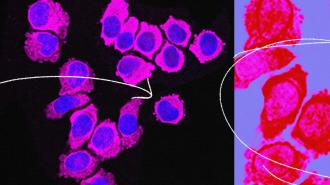

“One convincing and direct piece of evidence appeared when we placed one ILC2 and one tumor cell directly together and found that the tumor cell died, but the ILC2 cell survived,” said Yu. “This proves that the ILC2s directly killed the cancer cell in that absence of any other cell.”

Looking ahead: The way the ILC2s killed the cancer cells was unlike anything seen before, so understanding of how they work will be a focus of future research. The City of Hope team wants to test the cells’ ability to treat other health issues, including viral infections, too.

They’re particularly excited by the fact that, unlike some other immunotherapies, including CAR-T cell therapy, ILC2s don’t need to come from a patient’s own body to fight their cancer — healthy donors could provide the cells, which could then be multiplied, frozen, and administered off the shelf, right away, as needed.

This is assuming researchers are able to develop a safe, effective new immunotherapy from ILC2s, which will require a lot more work — but the City of Hope team is already ahead on that front.

“You have to be able to expand these cells for human clinical trials and one of the exciting things is that we are on the right track,” said Caligiuri. “At City of Hope, we have the advantage of access to our good manufacturing practices-compliant facilities that can manufacture cells for us and speed discoveries into clinical trials.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.