This article is an installment of Future Explored, a weekly guide to world-changing technology. You can get stories like this one straight to your inbox every Thursday morning by subscribing here.

Past studies have used the gene-editing technology CRISPR to remove genes from immune system cells to make them better at fighting cancer. Now, PACT Pharma and UCLA have used CRISPR to remove and add genes to these cells to help them recognize a patient’s specific tumor cells.

“It is probably the most complicated therapy ever attempted in the clinic,” study co-author Antoni Ribas told Nature. “We’re trying to make an army out of a patient’s own T cells.”

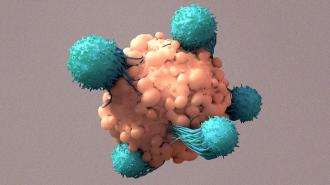

T cells are our immune systems’ built-in defense against cancer.

Natural cancer killers: Our bodies are made up of trillions of cells. These cells grow and multiply through cell division, and when they get old or become damaged, they die and new cells replace them.

Cancerous cells have genetic mutations that prevent them from dying when they should — instead, they multiply uncontrollably, potentially forming clumps or spreading to other parts of the body and crowding out healthy cells.

Our immune system includes a built-in defense against cancer: T cells. These are a type of white blood cell with proteins on their surfaces, called “T cell receptors,” that bind to specific foreign or cancerous cells, prompting the T cell to attack and kill them.

The challenge: T cells aren’t perfect, though.

In part because cancer cells look a lot like healthy cells, they’re adept at flying under the immune system’s radar. Tumor cells can also release chemical signals that make them even harder for T cells to identify.

“At some point the immune system kind of lost the battle and the tumor grew.”

Stefanie Mandl

Sometimes cancer cells are simply multiplying too fast for T cells to keep up.

“If [T cells] see something that looks not normal, they kill it,” lead author Stefanie Mandl, who serves as CSO of PACT Pharma, told Nature. “But in the patients we see in the clinic with cancer, at some point the immune system kind of lost the battle and the tumor grew.”

By genetically engineering T cells to be better at spotting proteins commonly found on the surfaces of blood cancer cells, researchers have been able to develop treatments — called “CAR-T cell therapies” — for people with those cancers.

No one has yet been able to find reliable, comparable proteins that work for solid tumors, though — each person’s cancer seems to be too unique for existing CAR-T cell therapies to be effective.

CRISPR boost: A small phase 1 study by researchers at PACT Pharma and UCLA suggests that we may be able to use CRISPR to boost the ability of our T cells to fight solid cancers.

They took blood and tumor samples from 16 patients with solid tumors in various parts of their bodies. Using genetic sequencing, they scoured the samples for mutations that were present in their tumor cells but not their blood cells.

“The mutations are different in every cancer,” said Ribas. “And although there are some shared mutations, they are the minority.”

“We’re trying to make an army out of a patient’s own T cells.”

Antoni Ribas

The researchers then searched each participant’s T cells, looking for ones with receptors likely to recognize the cancer’s mutations.

Using CRISPR, they knocked out a gene for an existing receptor and inserted a gene for a cancer-targeting receptor into T cells that lacked it. Once they had engineered what they thought would be enough T cells, the researchers infused them back into the patient.

The results: Later biopsies found that up to 20% of the immune cells in the patients’ tumors were the engineered T cells, suggesting that those cells were in fact very adept at homing in on the cancer.

Only two of the 16 participants experienced minor side effects — fever, chills, confusion — attributable to the T cells, but they quickly resolved.

“It is probably the most complicated therapy ever attempted in the clinic.”

Antoni Ribas

A month after treatment, five of the patients’ tumors were the same size as before, suggesting that the engineered cells may have had a stabilizing effect on their condition.

The cancer continued to progress in the other 11 patients, but the patient given the highest dose of cells saw a short term improvement in their cancer — that could mean the treatment would be more effective in future studies if administered in higher doses.

“We just need to hit it stronger the next time,” said Ribas.

The cold water: This small phase 1 suggests that the engineered T cells are safe and potentially effective, but there are still a lot of limitations to overcome.

One problem is that while the engineered T cells did tend to home in on the tumor, they didn’t always attack the cancer cells.

“The fact that you can get those T cells into a tumor is one thing. But if they get there and don’t do anything, that’s disappointing,” Bruce Levine, a professor of cancer gene therapy at the University of Pennsylvania, who wasn’t involved in the study, told WIRED.

Another is that the treatment is expensive, complicated, and time-consuming — it took the researchers a median of 5.5 months just to identify the mutations to target with CRISPR after sequencing a patient’s cells.

“You can build on this. You can make it better and more potent and faster.”

Katy Rezvani

Looking ahead: These hurdles aren’t insurmountable, and now that the researchers have shown that CRISPR can be used to engineer cancer-targeting T cells, future studies can take the approach to the next level.

“You can build on this,” oncologist Katy Rezvani, who wasn’t involved in the study, told Medical Express. “You can make it better and more potent and faster.”

One day, the engineered T cells might even allow doctors to protect their patients against recurrence while treating their existing cancer.

“We are reprogramming a patient’s immune system to target their own cancer,” Mandl told TIME. “It’s a living drug, so you can give one dose and ideally have life-long protection [from the cancer].”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.