Stanford researchers have finally figured out how a therapy that blocks a single protein can reverse age-related muscle loss in mice — and the discovery suggests seniors might not be the only ones who could benefit from it.

Age-related muscle loss: People tend to start losing muscle mass and strength in their 30s, and from 50 on, you could be losing up to 10% of your muscle mass every decade.

While it is possible to regain lost muscle through exercise, health issues can make hitting the weights a challenge. If left unaddressed, though, age-related muscle loss can lead to decreased mobility and weakness, which increases the risk of falls or other injuries.

“The old mice are about 15% to 20% stronger after one month of treatment.”

Helen Blau

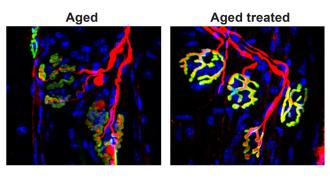

The background: In 2020, Stanford researchers discovered that blocking a protein called 15-PGDH in older mice for one month increased their muscle mass and strength. The mice could run longer, and their muscle cells started to look more like those of young mice.

“The improvement is really quite dramatic,” said senior author Helen Blau. “The old mice are about 15% to 20% stronger after one month of treatment, and their muscle fibers look like young muscle.”

The mystery: Prior to that study, the Stanford team had already figured out that a different molecule, called PGE2, triggers muscle stem cells to repair the tiny tears that exercise or injury create in muscle fibers, leading to increased muscle mass and strength.

They also knew that the 15-PGDH protein breaks down this beneficial PGE2 molecule and that our bodies make more of this protein as we get older — that’s what inspired them to try blocking 15-PGDH to reverse age-related muscle loss in mice.

What they didn’t know was why 15-PGDH levels increased with age.

“This leads to a faster recovery of strength and function.”

Helen Blau

What’s new? They’ve now published a study that suggests the loss of neuromuscular junctions — connections used to send signals from nerves to muscles, telling them to contract — as we get older is the trigger for the increase in 15-PGDH.

“We found that when you cut the nerve that innervates the leg muscles of mice, the amount of 15-PGDH in the muscle increases rapidly and dramatically,” said Blau. “This was an exciting new insight.”

“But what surprised us most,” she continued, “was that when these mice are treated with a drug that inhibits 15-PGDH activity, the nerve grows back and makes contact with the muscle more quickly than in control animals, and that this leads to a faster recovery of strength and function.”

Experiments on older mice — ones that had lost their neuromuscular junctions naturally to age, not surgery — confirmed that blocking 15-PGDH triggered the regrowth of the connections.

Looking ahead: Therapies that work in mice often don’t translate to people, and more preclinical research is needed to figure out whether blocking 15-PGDH in humans could lead to unwanted side effects.

“There is an urgent, unmet need for drug treatments that can increase muscle strength due to aging, injury, or disease.”

Helen Blau

Still, the researchers are hopeful they’ll be able to launch a clinical trial in the next year to see whether reducing 15-PGDH can help people with spinal muscular atrophy, a disorder that leads to a loss of neuromuscular junctions and muscle control.

They’re also exploring whether the treatment might be able to help people with ALS — another condition characterized by a loss of neuromuscular junctions — in addition to continuing their research focused on age-related muscle loss.

“There is an urgent, unmet need for drug treatments that can increase muscle strength due to aging, injury, or disease,” said Blau. “This is the first time a drug treatment has been shown to affect both muscle fibers and the motor neurons that stimulate them to contract in order to speed healing and restore strength and muscle mass. It’s unique.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.