Learning about the brain is a challenge. Neuroscientists must measure the operations of a byzantine tool with the very tool they’re attempting to measure. That’s a journey that’s not so much winding as it is Möbius, so it’s little wonder that history’s greatest scientists and philosophers have yet to crack, say, the hard problem of consciousness.

Other problems are limited more by our inability to poke around in real-time. Take the question of adult neurogenesis. Neurogenesis is the brain’s ability to generate new neurons. This process is intensely productive during embryonic development, and it continues after birth at a rate any parent with a toddler can appreciate daily.

For much of the 20th century, scientists believed neurogenesis didn’t take place in the structured, sedate brains of human adults. They thought that after development we possessed all the neurons we’d ever have, and this lead to a perception that aged minds had less plasticity.

Then studies began to accumulate evidence that the adult brain may not be as placid as thought. One such study, published in 2018 in Cell Stem Cell, autopsied the hippocampi of 28 adults and found human brains still churn out neural stem cells by the thousands well into our golden years.

“We found that older people have similar ability to make thousands of hippocampal new neurons from progenitor cells as younger people do,” Maura Boldrini, the study’s lead author, said in a release. “We also found equivalent volumes of the hippocampus (a brain structure used for emotion and cognition) across ages.”

Other studies have clouded the consensus. A study published in Nature, one with a remarkably similar methodology to Boldrini’s, found little evidence for young neurons in the dentate gyrus, a part of the hippocampus. Its authors concluded that neurogenesis likely ceased, or was extremely rare, in adults.

But a new study published in the Journal of Neuroscience may have discovered how adult brains can continue to mature and retain plasticity without producing bubbly, baby neurons at the same clip as their younger counterparts.

One challenge to understanding adult neurogenesis is that most studies examine new neurons within their typical six-week development window. During that time a neuron is born, travels to the region of the brain where it will work, and differentiates depending on that location. After that, the neuron is considered mature.

According to Jason Snyder, a researcher at the Djavad Mowafaghian Centre for Brain Health and one of the study’s authors, the researchers wanted to look beyond this window. They wanted to know if adult-born neurons could mature, grow later in life, and become unique to those produced by newborns’ brains.

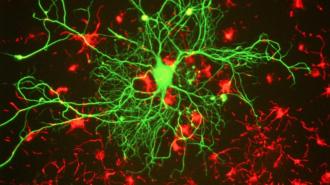

To test their hypothesis, the researchers injected a viral vector into lab rats’ dentate gyri. The retrovirus was tagged with fluorescent reporters. After it inserted a copy of its genome into the dividing cells’ DNA, subsequent generations would glow and allow the researchers to follow them.

They watched the rats’ adult-born neurons for the typical six weeks, but then kept observing into the seventh. Amazingly, the seven-week-old neurons continued to exhibit growth markers, such as larger nuclei and thicker dendrites. The researchers continued their watch for 24 weeks and found the aged neurons were bigger and sported more connections than infant-born ones.

Based on the results, they think that adult-born neurons may continue to contribute to plasticity and regeneration throughout life, even if cell production winds down with age.

“Our study is exciting because it gives us a new framework for studying these cells,” Snyder said. “Even if neurogenesis stops as we age, our study shows that it’s still relevant because cells take so long to mature and keep growing for so long. This is really just a different way of looking at them.

The challenge of measuring adult neurogenesis is difficult, but it’s not impossible. A big part of the solution is knowing what to measure and where. While this new study was performed on rats—and therefore may be a poor predictor of what we’ll see in humans—it can direct future research by showing neuroscientists where to look and what to look for.

And unlike the hard problem of consciousness, unraveling the mysteries of adult neurogenesis may have clinical applications. Better the lifecycle of neurons may reveal how neurological disorders such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease emerge. There’s even research linking disorders such as depression and anxiety to neurogenesis activity.

This knowledge may lead to new treatments, but if not, it could also reveal a better understanding of how our lifestyles and environments support brain health and regeneration throughout human life.

This article was reprinted with permission of Big Think, where it was originally published.