UC Berkeley scientists have trained an AI to reconstruct a song using just the brain activity of a person listening to it — and in the process, they learned things about the brain that could unlock better thought-to-speech systems for people who can no longer talk.

The challenge: Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) are increasingly helping people regain their voices after injuries or diseases — with proper training, the systems can often determine what a person is trying to say based on their brain activity, and a computer-generated voice can then speak for them.

However, while speech BCIs might be able to decipher many of the words people want to say, they miss the musical elements of speech, such as rhythm, stress, and intonation, that we use to convey meaning while talking to one another.

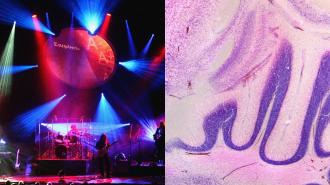

What’s new? Researchers at UC Berkeley have developed an algorithm that was able to reconstruct a song — Pink Floyd’s “Another Brick in the Wall, Part 1″ — from the brain activity of a person listening to it.

The discoveries could lead to speech BCIs that decipher both what a person is trying to say and how they want to say it.

This is the first time anyone has managed such a feat, and it revealed new insights into how the brain processes music — the researchers identified parts of the brain that detect rhythm, for example, and discovered that the areas that respond to the onset of vocals aren’t the same as those for sustained vocals.

They believe these new insights could aid the development of speech BCIs capable of deciphering both what a person is trying to say and how they want to say it.

“[This] gives you an ability to decode not only the linguistic content, but some of the prosodic content of speech, some of the affect,” said lead researcher Robert Knight. “I think that’s what we’ve really begun to crack the code on.”

How it works: The brain activity recordings used to train and test the new AI were obtained from 29 patients at Albany Medical Center who’d had electrodes placed on the surfaces of the brains to help their doctors pinpoint the locations of their epileptic seizures.

While the electrodes were in place, the patients were asked to listen attentively to a three-minute segment of “Another Brick in the Wall, Part 1,” not focusing on any particular aspect of the song.

Brain activity recordings from when the patients listened to about 90% of the song were then used to teach an AI that certain brain activity corresponded to certain audio frequencies.

The AI was then tasked with using the brain recordings to reconstruct the remaining 10% of the song, and while its recreation isn’t a note-for-note replica of the original, the song is clearly recognizable.

Looking ahead: Knowing that certain parts of the brain are activated when a person listens to music doesn’t necessarily mean those same parts will light up if a person is trying to give their own words a bit of extra flair.

Still, the UC Berkeley team is hopeful that the newly identified connections between music and brain activity might aid the development of speech BCIs that can more accurately recreate what a person is trying to say.

“As this whole field of brain machine interfaces progresses, this gives you a way to add musicality to future brain implants for people who need it,” said Knight.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.