A team of researchers from across the globe has banded together to achieve a massive undertaking: a global map of ant species.

The map is over a decade in the making, combining almost 1.5 million records gleaned from a mountain of studies, museum archives, and field work.

With the help of AI, the researchers turned that constellation of data into a global map showing the richness of ant species diversity and which ant species have the smallest ranges — making them most vulnerable and potentially in need of conservation efforts.

“This is a massive undertaking for a group known to be a critical ecosystem engineer,” Robert Guralnick, curator of biodiversity informatics at the Florida Museum of Natural History and study co-author, said.

“It represents an enormous effort not only among all the co-authors but the many naturalists who have contributed knowledge about distributions of ants across the globe.”

It’s an ant’s world: Invertebrates like ants underlie, quite literally, nearly all terrestrial ecosystems.

“Invertebrates constitute the majority of animal species and are critical for ecosystem functioning and services,” the researchers wrote in their study, published in Science Advances.

But despite their omnipresence and importance, our understanding of them is limited. Identifying hotbeds of ant species’ diversity and how many ant species there are is critical knowledge for helping to protect them.

To help fill in the gaps, the researchers turned to the wealth of data collected about ants over the years, using AI algorithms to help make sense of it — a difficult task, as all of the 14,000 known ant species had varying amounts of data available.

Ant AI: Most records the team found had location information included with it, but it was not always precise enough to plug into a map.

Piecing together an ant species’ range required the help of computational workflows, which estimated locations and checked for potential errors.

“Without a base of experts to consult for each species, we need to rely heavily on computational approaches to overcome several challenges in assembling a map of global diversity,” the researchers wrote in their paper.

The team first needed to gather their data from literature, museum collections, and species databases — and “often obscure” ones, at that. Once they had it, the data needed to be analyzed and checked for accuracy, then plugged into the algorithm to get their range estimates. Finally, they needed to smooth out the unevenness of the data with the help of a machine learning AI.

“Some areas of the world that we expected to be centers of diversity were not showing up on our map, but ants in these regions were not well-studied,” Jamie Kass, a postdoctoral fellow at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology and co-first author said.

“Other areas were extremely well-sampled, for example parts of the USA and Europe, and this difference in sampling can impact our estimates of global diversity.”

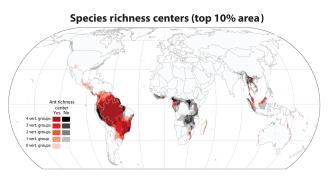

A “treasure map”: What the team ended up with were global heat maps broken into 20x20km squares.

The map shows an estimate of the number of ant species in each square, which they dubbed the “species richness;” the map also shows the number of ant species with small ranges per square, measuring species rarity.

The team found that only a small percentage of the most diverse ant regions already had some form of environmental protection, like parks or reserves. Of the top 10% most diverse areas, fewer than one in six had safeguards in place.

“Clearly, we have a lot of work to do to protect these critical areas,” Evan Economo, senior author and professor at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology, said.

Researchers can use the maps to not only identify what ant species in a given range may be at risk but also to guide conservation efforts.

By adjusting the data to replicate what would happen if the whole world were surveyed equally thoroughly, the team could also intuit where we should search next for undiscovered ant species.

“This gives us a kind of ‘treasure map,’ which can guide us to where we should explore next and look for new species with restricted ranges,” said Economo.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.